An Update on US-China Trade

Originally written in support of a Harvard Business School course

Trade between the United States and China began in 1784 with the Empress of China making its first trip to Canton, China. From this initial voyage grew many years of trade that varied in both type of goods and extent of trading. After a peak in opium trading and the Opium Wars between China and Great Britain, trade over the next century slowed and then even ended for about three decades starting in 1950.1 In 1979, the United States and China normalized diplomatic relations and trade began growing again. In 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization and trade between the two countries surged. From about $100 billion in 2001, U.S. imports from China grew to over $550 billion in 2022.2

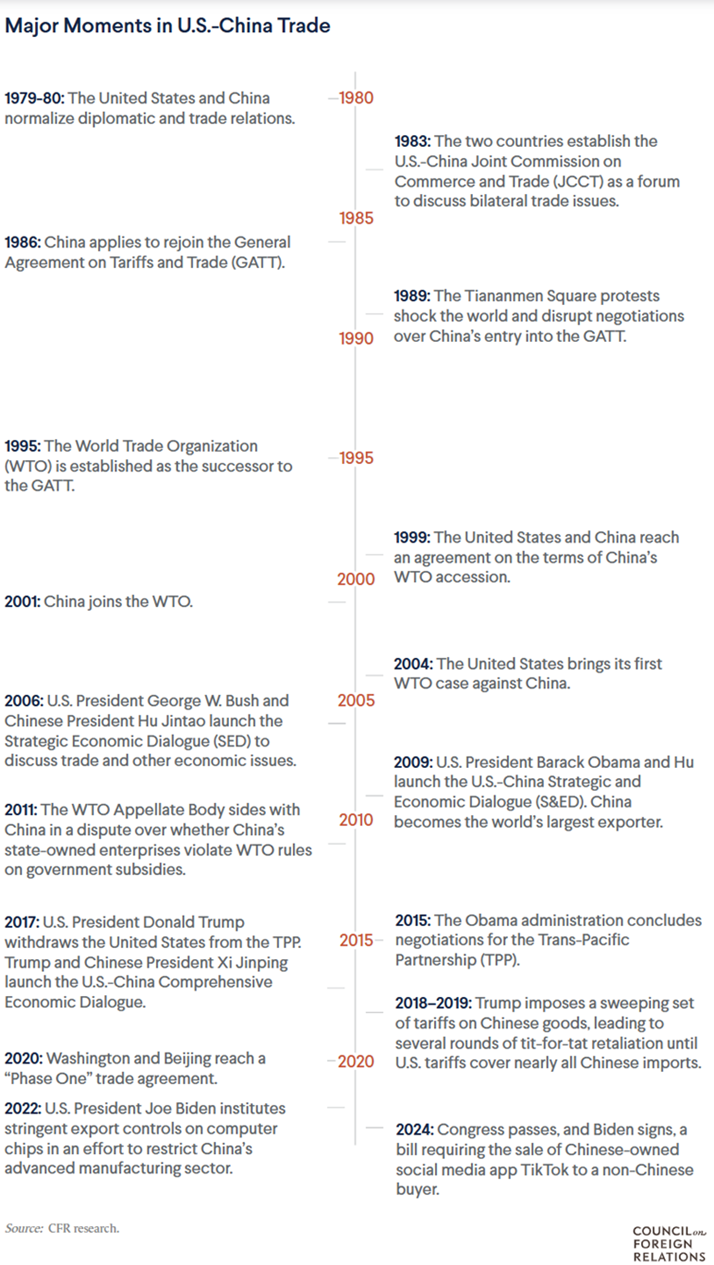

In the decades following China’s acceptance into the World Trade Organization and arrival on the global trade stage, the impact of the large increase in goods led to a “China Shock” to some other countries including the United States. This rapid increase in supply could be felt by consumers in lower prices but also lead to localized negative impacts for workers in competing industries.3 Figure 1 provides a timeline of major events in the development of trade between the United States and China. After two decades of growth, trade between the two countries peaked in 2022. The U.S. good trade deficit with China was $382.3 billion in 2022, 8.3 percent greater than in 2021. U.S. goods exports to China was $154.0, up 39 percent from 2012, and U.S. goods imports from China were $536.3 in 2022, up 26 percent from 2012. China represented about 7.5 percent of all U.S. exports in 2022.4 In 2023, China was the 4th largest U.S. good trading partner, with a total trade of $575 billion. China was the second largest source of imports at $427 billion in 2023. The total U.S.-China good trade fell about 17 percent from 2022, with U.S. exports down about 5 percent and imports down 20 percent due to China’s economic slowdown and supply chain shifts out of China.5

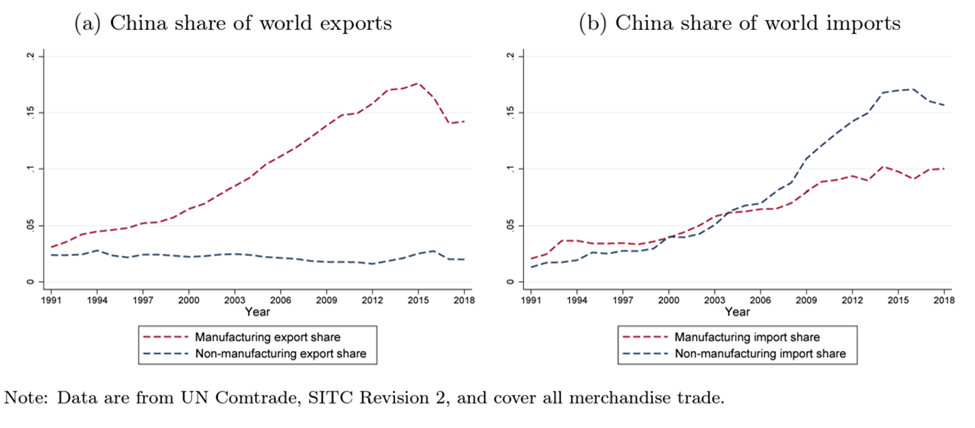

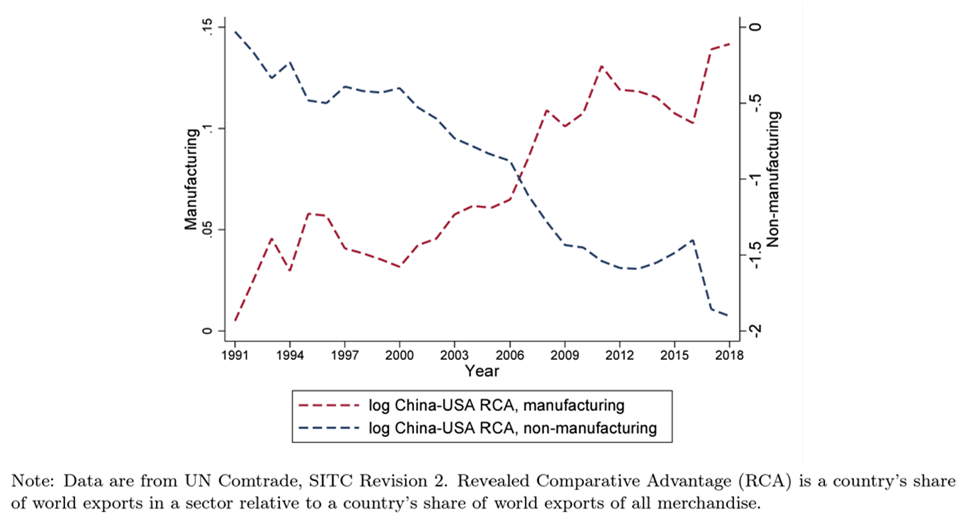

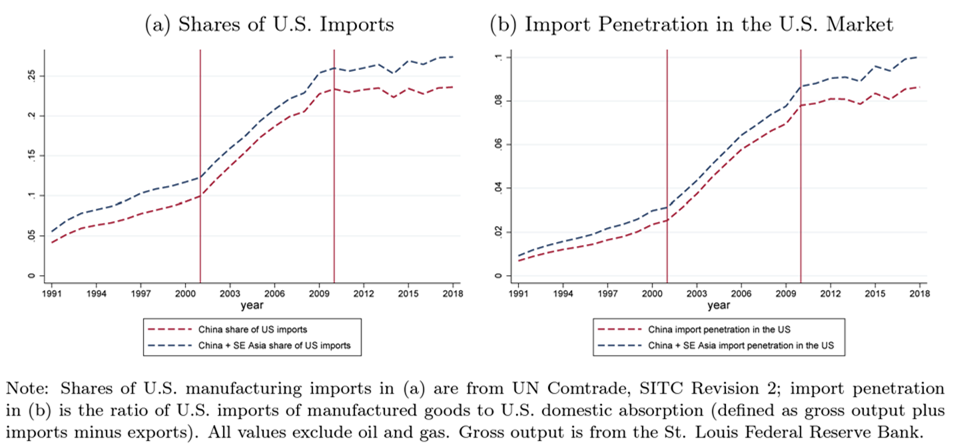

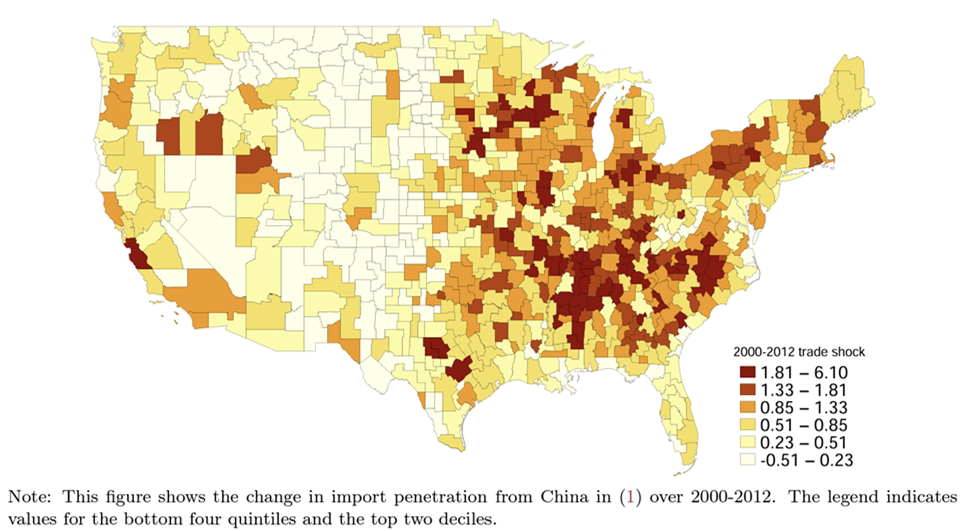

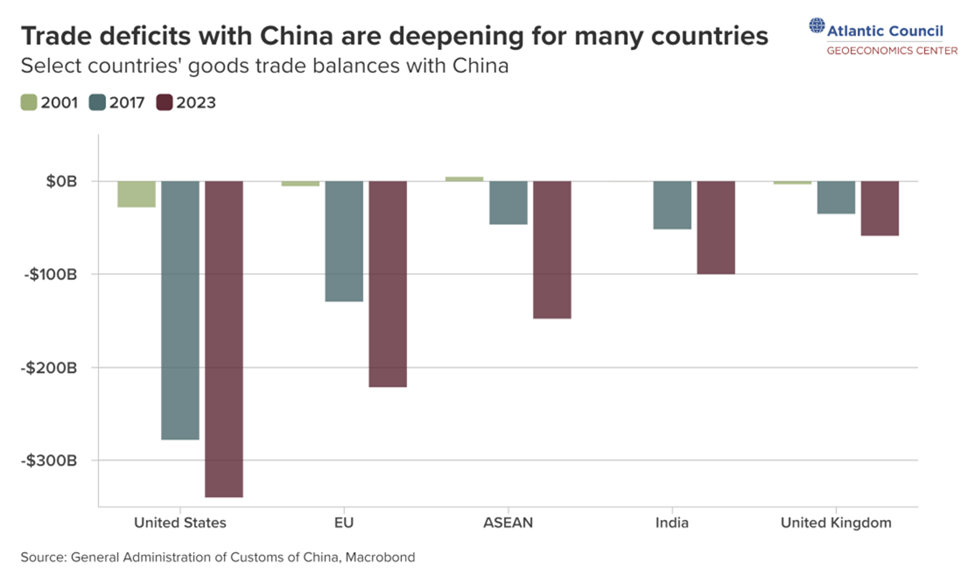

As trade with China grew over the last few decades, China revealed a specialization in manufactured goods products. Figure 2 shows China’s share of world trade by sector, illustrating a growing share of manufacturing exports since 1991. Figure 3 shows China’s revealed comparative advantage, illustrating the preference for exporting manufactured goods versus non-manufactured products. In Figure 4, it is possible to see the outsized proportion of U.S. imports from China as compared imports from all of Southeast Asia from 1991 to 2018. This graph shows the largest growth in imports occurred from about 2001 to 2010. Figure 5 plots the impact from this “China Shock” on regions of the United States, indicating how the effect of displacing U.S. domestic manufacturing could be localized to specific parts of the country. The growing trade deficit trend with China was not exclusive to the United States—Figure 6 shows growing trade deficits for various countries and regions.6

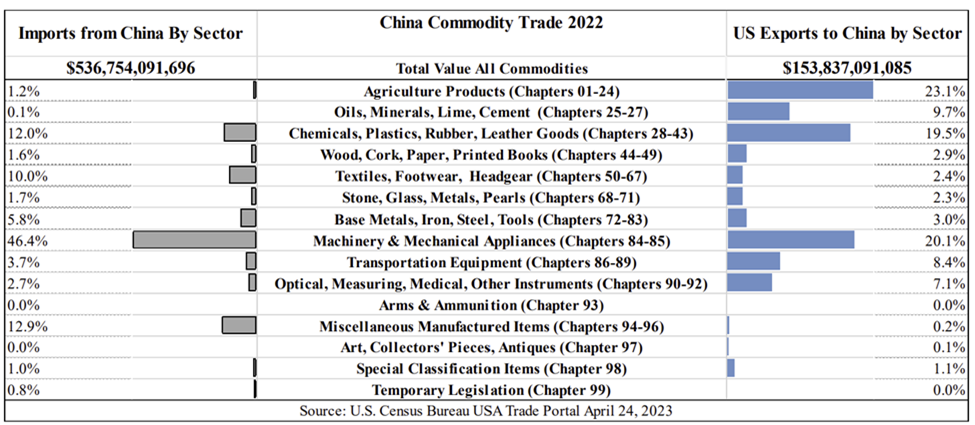

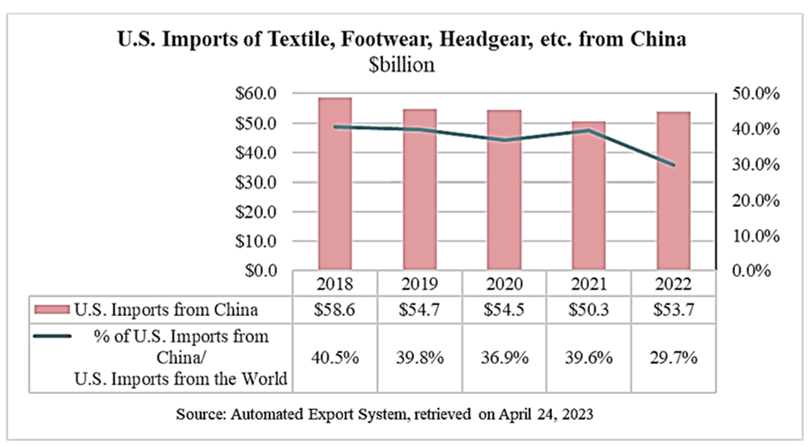

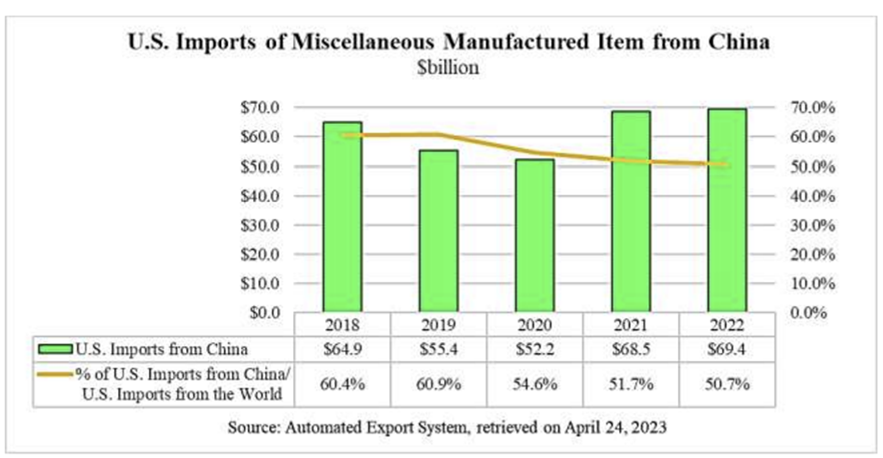

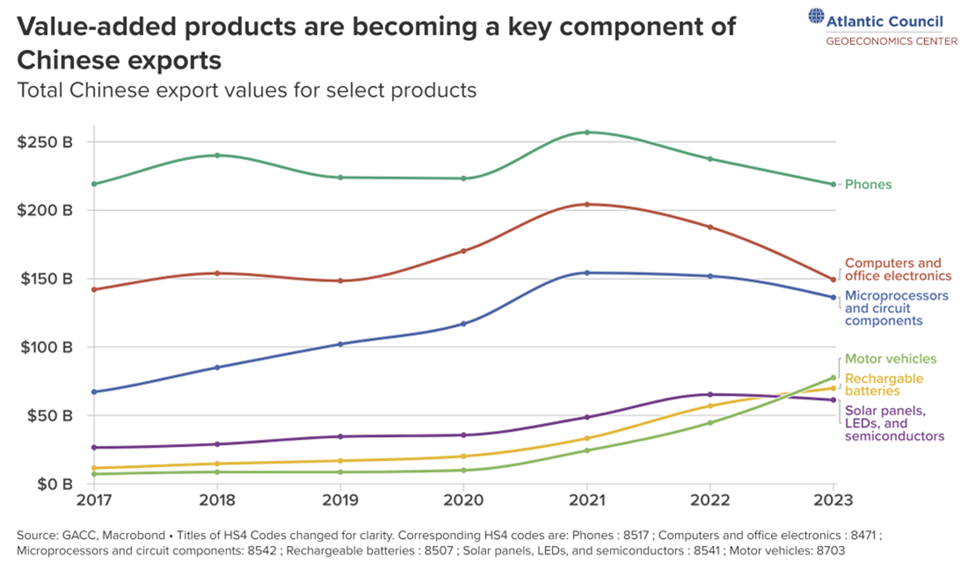

Though the Chinese export product mix has been changing slightly over time, it is still rooted in low-cost goods. Figure 7 shows a breakdown of U.S. imports and exports with China by commodity. In 2022, the top commodity sectors were, Machinery and Mechanical Appliances (46.4% of total U.S. imports from China), Furniture, Bedding, Lamps, Toys, Games, Sport Equipment, Paint, and Other Miscellaneous Manufactured Items (12.9%), and Chemicals, Plastics, Rubber, and Leather goods (12.0%).7 Figures 8 and 9 illustrate changes in the trade of two of these categories, showing a reduction in percentage of U.S. imports coming from China as compared to the rest of the world, even though the absolute value of imports remains nearly constant or increases. At the same time, Figure 10 shows the Chinese export mix also including move value-added components over time.

In 2016, Donald Trump was elected President of the United States, and a significant portion of his platform was based on competing better with China. Previous administrations had imposed tariffs targeted on goods that the U.S. claimed China was dumping at artificially low prices, blocked Chinese acquisitions on the basis of national security and on the recommendation of CFIUS, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States. President Trump took a stronger stance, believing that China posed larger challenges to the United States national interests in both the economic and political spheres, a sentiment captured in his administrations 2020 U.S. Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China Report below:8

“When the PRC acceded to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, Beijing agreed to embrace the WTO’s open market-oriented approach and embed these principles in its trading system and institutions. WTO members expected China to continue on its path of economic reform and transform itself into a market-oriented economy and trade regime.

These hopes were not realized. Beijing did not internalize the norms and practices of competition-based trade and investment, and instead exploited the benefits of WTO membership to become the world’s largest exporter, while systematically protecting its domestic markets. Beijing’s economic policies have led to massive industrial overcapacity that distorts global prices and allows China to expand global market share at the expense of competitors operating without the unfair advantages that Beijing provides to its firms. The PRC retains its non-market economic structure and state-led, mercantilist approach to trade and investment. Political reforms have likewise atrophied and gone into reverse, and distinctions between the government and the party are eroding. General Secretary Xi’s decision to remove presidential term limits, effectively extending his tenure indefinitely, epitomized these trends.”

Given this understanding, the Trump administration raised tariffs on certain imports, like 10% on aluminum and 25% on steel from all suppliers, citing national security concerns.9 Over the next few years, China and the U.S. went back and forth with various tariffs and restrictions. In 2019, Trump announced a Phase 1 deal that would remove some tariffs in exchange for an agreement from China to purchase an additional $200 billion worth of U.S. goods—an agreement it did keep.10

Following the general trend, President Biden took additional steps to bolster economic competition with China. He retained many of the existing tariffs and raised some of the rates. He also signed legislation that could ban China-owned TikTok and signed regulations into law that contained some of the most significant industrial policy implications of recent memory. The 2022 CHIPS and Science Act and 2022 Inflation Reduction Act included sections that pushed substantial government funding into research and development for specific critical industries, increased infrastructure investment significantly, and included incentives for domestic procurement. In his 2022 National Security Strategy, Biden elaborated:11

“Our strategy toward the PRC is threefold: 1) to invest in the foundations of our strength at home – our competitiveness, our innovation, our resilience, our democracy, 2) to align our efforts with our network of allies and partners, acting with common purpose and in common cause, and 3) compete responsibly with the PRC to defend our interests and build our vision for the future.”

Biden’s Secretary of State Antony Blinken added in a 2022 speech:12

“Economic manipulations… have cost American workers millions of jobs. And they’ve harmed the workers and firms of countries around the world. We will push back on market-distorting policies and practices, like subsidies and market access barriers, which China’s government has used for years to gain competitive advantage. We’ll boost supply chain security and resilience by reshoring production or sourcing materials from other countries in sensitive sectors like pharmaceuticals and critical minerals, so that we’re not dependent on any one supplier. We’ll stand together with others against economic coercion and intimidation. And we will work to ensure that U.S. companies don’t engage in commerce that facilitates or benefits from human rights abuses, including forced labor. In short, we’ll fight for American workers and industry with every tool we have – just as we know that our partners will fight for their workers.”

— See this post for the situation in 2021

Footnotes

-

Two Hundred Years of U.S. Trade with China (1784-1984),” accessed 11/11/24. Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University. ↩

-

The Contentious U.S.-China Trade Relationship,” last updated 5/14/24. Council on Foreign Relations. ↩

-

On the Persistence of the China Shock,” published October 2021. D. Autor, D. Dorn, G. Hanson. National Bureau of Economic Research. ↩

-

“The People’s Republic of China: China Trade and Investment Summary,” accessed 11/11/24. Office of the United States Trade Representative. ↩

-

“U.S.-China Trade Relations,” updated 8/8/24. K. Sutter, Congressional Research Service. ↩

-

“Why the next trade war with China may look very different from the last one,” published 8/22/24. M. Bhusari. Atlantic Council Geoeconomics Center. ↩

-

“U.S. Trade with China,” accessed 11/11/24. U.S. Department of Commerce Office of Technology Evaluation. ↩

-

“U.S. Strategic Approach to the People’s Republic of China Report,” published May 2020. U.S. Government. ↩

-

“Timeline: Key Dates in the U.S.-China Trade War,” published 1/16/20. Reuters. ↩

-

“The Contentious U.S.-China Trade Relationship,” last updated 5/14/24. Council on Foreign Relations. ↩

-

“National Security Strategy,” published October 2022. U.S. Government. ↩

-

“The Administration’s Approach to the People’s Republic of China,” speech given 5/26/22. Antony Blinken. ↩